A spate of events over the past year have made clear to us that the misplacement of Hipkiss* within the sphere of ‘Outsider art’/’Art Brut’ (sub-defined as amateur art), creating what has become a confusing parallel identity, must be laid to rest once and for all. In short, we are full-time professional artists, reliant on sales and funding for our livelihood, with no qualification whatsoever for the genre or any of its subgroups. Dealers, galleries or academics who include us under these labels are either poorly informed, or aware of the deception and acting in their own self-interest, financial or otherwise.

For those interested in a close-up take on the darker side of this wild west of the commercial art world – the lack of expected professional etiquette towards artists or knowledge of their rights as creators, the willingness to bend facts to suit the required narrative and thus sell work under false pretenses to trusting collectors, and how some of its actors managed to take an artist such as Hipkiss hostage for a time – read on.

*Pseudonym of artist duo comprising Alpha and Christopher Mason, historically known collectively as ‘Chris Hipkiss’. For those who might have stumbled on this page without knowing who or what a ‘Hipkiss’ is, a biography can be found here (link opens in new window).

Note for the uninitiated: this category is unique within art classification in that it depends not on style, technique or aesthetic but solely on a particular set of elements in an artist’s biography. In our own words, as quoted by Vayavya magazine in 2015, they include being: “male, solitary, preferably mentally ill, poorly educated, possibly incarcerated. Preferably dead”.1 Artists so labelled are also assumed to be amateurs, i.e. not to expect, or rely upon, the exhibition and sale of their work. Some proponents attempt to extend the definition to cover anyone who did not graduate from a conventional art school, but this logic is flawed in that many mainstream artists share such a background. Moreover, a look at the documentation for any exhibition or publication focused on the field invariably demonstrates that the curation is based only on the alleged ‘marginalisation’, lack of artistic evolution/intent and mental health of the artists (there are also racial subtexts to some definitions that are beyond the scope of this text – see ‘Further reading’).

It is a field that’s therefore also unique in the sense that a living artist is the party best qualified to reject their inclusion on demonstrating that they do not have the requisite biography. Generally speaking, if someone is in a position to write, and chooses to write, a rebuttal such as this, they do not belong in the ‘Outsider‘/’Art Brut’ category (and while devotees might quibble over semantics, the former is a working translation of the latter; to us and the rest of the world, they are the same thing). Moreover, to apply such a label to an autonomous living artist without positive consent should be considered defamatory.

In 1991, eight years into our partnership, we found ourselves at a crossroads. Christopher was reappraising his options, having declined a place as the younger sibling in the family business hierarchy. Meanwhile Alpha was forced to abandon a lucrative but demanding career as a freelance IT consultant following a prolonged viral illness and subsequent ME diagnosis. It was a time of re-evaluation, not just in terms of new limitations but also of a new sense of freedom. While Christopher devoted time to local nature reserves and considered a professional life in conservation, Alpha wrote the first draft of a novel, taught herself darkroom techniques and toyed with the idea of a career in journalism. We also had shared creative aspirations and abilities which we were able to begin to shape and nurture in earnest. All we learnt individually was gradually pooled into our joint efforts.

However and with hindsight, at this comparatively early stage of our relationship, we were still subject to society’s unwritten rules of individualism; at that time, we had a tendency to try to divide our creative pursuits in terms of identity even while working on them together. In our eyes, this served a potential purpose in enabling one of us to promote the other in a certain field. We also enjoyed inventing pseudonyms and alter egos, often combining one of our first names with a random surname; it was part of the fun. In those early years, we sometimes made art signed with two such names together (Iskander and Hipkiss). It would take a few more years for us to abandon the perceived barrier between us and redefine ourselves as an indivisible duo under one name, but life moved ahead of us in the interim.

We went through a process familiar to any creative attempting to find a foothold in the professional world. In the case of our art, we spoke to anyone who’d listen, wrote to art critics and museum curators, and trawled around small galleries in London. Also like many others, the actual quality of our portfolio was with hindsight sub-optimal and the quantity of works unimpressive. In addition, we were (and are) specialists in drawing, a medium that was not to take its own place in the contemporary art world until the following century. However, artists Rose Wylie and Roy Oxlade were near neighbours of ours and offered good advice, then a friend of a friend in our Kentish village – a portrait artist called Madeline Ireland – saw something in our work. She knew the owner of a small gallery in London and that was where we started.

In parallel, we were pursuing outlets for our other endeavours, such as writing and photography, and thinking about a return to higher education. It was only by chance that our efforts on the art side reaped the first tangible reward.

And so it was that, at the end of 1992, and at a very, very early stage in the development of our art and public identity, the owner of the small contemporary gallery in London – Sweet Waters – commissioned a set of work for our first show. At that point, we were making anarchic, cartoonish drawings inspired by our environmentalist and political preoccupations and the Riot grrrl movement. Our art career could have gone in any direction, or simply fizzled out.

However, in what turned out to be a fateful moment, we met John Maizels, the editor of Raw Vision magazine, at a contemporary art fair for which the gallery owner had given us tickets. He liked the work, undoubtedly attracted by its undeveloped quality, and offered us an article in his magazine, to be written by and about us. It was published in the summer of 1994.

In those days, the magazine was a fledgling indie publication whose scope included a range of what might literally be termed self-taught art.2 It had never occurred to us to consider ourselves ‘self-taught’; in fact, it was an odd concept for two people who had both declined places at art college for well-considered reasons that had nothing to do with a lack of support or opportunity to pursue that path. Firstly, we had an array of other choices, but we also knew friends and family who had chosen to study art and felt that the experience had stifled their creativity rather than enhanced it. We no longer believe that to be an inevitable outcome, and certainly missed out on the many elements of study that might have helped us navigate our career.

To us, the article was a little project – a chance for us to publish something under Alpha’s name and publicise our art at the same time. The idea that it should pigeon-hole us then – let alone still be affecting us almost thirty years later – would have been unbelievable at the time and would have resulted either in our refusing the brief or writing it in a very different way.

In pre-internet days, researching what was a very niche domain at the time was virtually impossible, so we were reliant on its partisans for any information. Even the word ‘Outsider’ had for us the connotations it does for most people: maverick, cool, original, not following the pack. Though these attributes may apply to some artists labelled as OA, they are most certainly not the main expected characteristics – and little did we know that we had become unwittingly embroiled in a kind of ‘recruitment drive’ to keep the field fresh with new names. Our mere appearance in Raw Vision was more than enough for some to absorb a version of Hipkiss unrecognisable to us.

Due to our being both subject and writer, the article also forced a perceived separation of us as a couple. For the ensuing 17 years, our way of dealing with this without excluding Alpha completely was to refer to her as an ‘agent’, in line with our earlier notions of how best to work as a couple. Some might also remember Christopher referring to Alpha as the ‘shading consultant’, an apparently lighthearted reference with deeper meaning. We became so tired of being dragged apart at vernissages – Christopher surrounded and feted as a singular ‘maestro’ while Alpha was quizzed on how she managed to live with his assumed mental condition – that we once attended an opening handcuffed together.

It was, of course, absurd and inappropriate that we should have been packaged and stamped at the time of our very first show – an exhibition we’d worked hard to achieve, in a mainstream gallery – as a ‘classic art brut’ artist (to quote a Parisian dealer as recently as 2019). We were two young people, from relatively privileged, educated backgrounds; we perceived ourselves as active and self-determining in our life and choices; we made art because we wanted to be artists. We were the absolute antithesis of the ‘Outsider artist’. But we reckoned without the locomotive that the commercial OA world was becoming.

At first, in the 90s, we were labelled ‘Visionary’ or sometimes ‘Folk’. In France, we tolerated ‘Singulier’, another term that was at least not biography-dependent. None of these described us or our work, but they did not carry the connotations of OA. However, with the advent of the internet after 2000, such relatively benign categories were subsumed under the more-loaded OA banner. Since that time, ‘self-taught’ (now with a capitalised first letter) has also become a synonym for ‘Outsider Art’, and Raw Vision an international reference for the latter.3

We were not passive victims to the process. Within months of writing the RV article, we’d been well aware that the OA label was utterly inappropriate in our case. We first publicly denounced it, to a journalist writing a Sunday broadsheet piece, in 1995 and continued to do so at any available opportunity.4,5,6 We quickly learnt to identify the biggest sharks in the pond too (no offence to sharks intended).

One such suggested, even before the publication of the Raw Vision article, that we donate a large work to the best-known OA collection in Europe at the time – bearing in mind that we were then unknown to anyone in that world. His reasoning, of course, was that an accepted gift would justify his selling our work at inflated prices. We rejected his proposal, as much because we couldn’t countenance parting with a year’s work for nothing as because we were suspicious of the nature of the collection.

We did, however, sell this gentleman a work for a pittance and consign him several more. Once we discovered that he’d immediately sold the first one for several times what we’d been paid, we ceased contact with him – which hasn’t stopped him occasionally offering any of our work that comes his way for sale, under the OA label, with our obsolete pseudonym, to this day. He is not the only OA dealer willing to exploit the ease with which a fledgling artist – especially one who has not been through the college system for whatever reason – can be parted from their work on a promise.

In the UK, we have been represented only by contemporary galleries. Elsewhere, we made several mistakes with galleries and dealers, hoodwinked by the fact that they knew we had no OA credentials. We reckoned without the willingness of many to forge ahead with a presentation of an artist like us as OA despite that. Some bought work directly, only for it to turn up later in an OA collection; some of these are still labelled as such. Others, such as a Parisian gallery with whom we mounted one solo show when its stable included only ‘singulier’ artists, morphed into different, specialised entities and took Hipkiss along with them despite our objections. In the case of the Paris gallery, for some reason we were the only artist in the original stable not to be dropped when the gallery changed its name and ethos.

Looking back, we have often castigated ourselves for allowing our embrace by exponents of the field, but, on objective recollection, realise that we cannot be held accountable to the degree some have tried to suggest. A prominent example, Monika Kinley (see below), who bought a number of pieces during the 90s, was instrumental in having our work shown in several prestigious (mainstream) venues in which we had control of our presentation. We had good reason to believe we were different, in her eyes, from the dead artists she and her late husband had identified as fitting the OA mould. We spent many hours with her and considered her a friend, discussing everything from art to politics and our personal histories, not to mention our own artistic aspirations; yet, years later, she was to portray Christopher as a lowly (and solitary) simpleton in her autobiography7.

Whether this kind of behaviour was intentionally duplicitous, or merely a result of sloppy methods in the pursuit of a self-agrandising goal, we will never know. In any case, many of those who have become the self-styled experts of the field displayed both a desire to make their own legacy out of others’ art and a lack of rigour in assembling it. Some have become so-called ‘references’ of the field – vaunted arbiters of who belongs – despite an absence of any scrutiny of their qualification to assume such a position.

The galleries broadly within the self-taught orbit with whom we chose to work for a number of years – Cavin-Morris in New York and Delmes & Zander in Cologne – never represented us as anything other than contemporary artists. Though Cavin-Morris took our work to the New York Outsider Art fair in the 90’s and early 2000’s, once the discourse crystallised in the mid-2000’s, we mutually agreed that it was not appropriate. (The fairs are an interesting example of how OA ate its neighbours after the turn of the century, and luminaries including the curator of the OA department at Christie’s have seen fit to incorrectly label artists such as us with the catch-all on the simple basis that they bought a small Hipkiss there once.)

Certain institutions connected to the OA world have also been allies: JMKAC and the Kohler Foundation, for example, who have collected a number of our larger works, do not confine themselves to a genre and make efforts to treat art on its own merits and its creators as diverse and evolving. A number of more strictly-defined organisations have simply acknowledged the inappropriateness of including an artist like us in their collections. The genuine arbiters of the field do not crowbar living artists into it, because doing so risks undermining any respect for it; including people like us makes a mockery of the label.

Nina Katschnig, director of Galerie Gugging, deserves a special mention. A dealer of OA deposited a small collection of our work with her with the intention that it be featured in a group exhibition entitled ‘Global Art Brut’; this would have been an abuse of our legal rights, particularly as we had expressly vetoed his idea several times. Instead, Nina worked with us to mount a two-person show with Anna Zemánková, an artist of whom we are great admirers. In common with a number of those connected to centres working with what one might term real ‘Art Brut’ artists – i.e. fulfilling Dubuffet’s definition and producing work within art therapy contexts – she decries labeling altogether.

Other notable voices of sanity came from the likes of Roger Cardinal (the original translator of Dubuffet’s ‘Art Brut’ into ‘Outsider’) who told us directly that he was bemused by attempts to include us. Jane Kallir of the prestigious Galerie St. Etienne in New York, whom we met in 1998, later wrote specifically about the non-fit of Hipkiss.8 Later still, James Brett, the creator of The Museum of Everything, discussed with us our miscategorisation and its bearing on his decision not to try to include us in his project. Numerous journalists and reviewers have expressed scepticism, puzzlement – and sometimes the suspicion of Hipkiss as a willful imposter or impersonator – with respect to our inclusion in OA shows, etc.9,10,11

However, various museums, writers and galleries did so label us, often without our prior knowledge or under the faulty ‘broad church’ pretext, and despite the abundant and freely-available evidence of us as living, contemporary artists. Without wishing to imply intentional ill-will on the part of the curators, etc., or lack of appreciation on our part for the efforts some went to to showcase our work12, when dealing with what amounts to personal judgements on living people, more care is required. [For an update concerning a shocking case of this behaviour that has occurred in 2023, see note 13 below.]

A major issue with these labels, as well as the ‘broad church’ logic, is that their literature tends to make blanket statements regarding the mental state and intentions (or lack thereof) of the artists. Whilst no-one has lied outright by inventing a specific mental health diagnosis in our case, quite a number have tried to paint a picture of social marginalisation, and among the myth-makers were those people with whom we had socialised as intellectual equals, or the dealers we had met and who were well aware of our lack of ‘credentials’ for the field. Their “Chris” (always the familiar terminology, and no mention that Hipkiss was a pseudonym) was variously: an obsessive who used art as self-prescribed ‘therapy’; a guileless ‘common handyman’ who created art by accident; or some variant of the idiot savant.

Implications such as these, in most spheres of public life, are not to be made flippantly; without positive supporting evidence and/or affirmation by the subject themselves, they’re considered derogatory. However, in this commercial backwater of the art world, many of its champions are more than willing to wander into defamatory territory. We would advise anyone exploring it to do so with an awareness of this tendency.

As a side-note, the difficulties of those suffering from mental illness are quite familiar to us, not only due to having a close relative afflicted with bipolar disorder that curtailed their life and affected everyone in the family; we also assumed the role of primary carers, for several years, for a formerly-very-talented artist friend who had developed schizophrenia. We tried everything we could to try to help him find a way through life. We know all too well the real obstacles faced by those confronting these conditions. To witness the casual and cynical application of medical diagnoses for the purposes of selling art is extremely troubling.

Another expression we’ve heard increasingly over the years to justify someone’s inclusion in the genre is a ‘lack of privilege’. This has even been said, directly, about us. As with the pitfalls of using a mental health condition as an identifier, this is dangerous territory that only those with the luxury of supreme privilege on the world stage would dream of broaching so readily. We alluded to this subject above, but to unpick it in our case:

We both grew up in south-east England, the wealthiest part of the UK. Our households were headed by two parents in a stable marriage throughout our childhood and early adulthood, both marriages ending only on the death of one spouse. Christopher’s family was very comfortable financially, Alpha’s moderately so. In the UK, only a tiny elite pay for schooling; like most academically-able kids, we benefited from a free, high-quality grammar-school education (the popular notion of Christopher ‘quitting’ school at sixteen omits the fact that he went on to study a specialist, technical set of subjects to enable him to join the family business). The state equally paid (twice, in Alpha’s case) for our university tuition and – in those days – also provided a grant for living expenses. We are a white and ostensibly heterosexual couple. We hopped onto the property ladder aged 22 and own two houses.

One can only imagine how laughable – not to mention insulting – a description of us as ‘under-privileged’ would seem to 95% of the world’s population. Yet the determination of some to shoehorn artists into their pigeon-hole at any cost leaves logic and reason as less than afterthoughts.

Some have understandably questioned why we didn’t simply refuse to go anywhere near galleries within the orbit of the categorisation. The simple answer to this is that contemporary galleries and curators naturally assume that artists claimed under the banner are incommunicado, or dead, or that their work does not evolve in the way that one would expect of a ‘normal’ artist. The above history, with its ‘frog in a saucepan’ elements, goes some way to describing how we were caught in the trap. But there were personal reasons in our case too…

In the early days, we’d both gone back to university and were considering careers in academic research. The myths being built up around the pseudonym, on both sides of the Atlantic, seemed beyond our control and, unsettling though they were, we didn’t assume that art would be any more than one strand of our professional life. Significantly, the inferences of the field dictated that we distanced Alpha ever further from the artistic identity due to the sensitive nature of her doctoral studies, and despite her ongoing artistic input.

In the late 90s, our attentions were taken up with family matters; Christopher’s mother died in 1997, following a battle with leukemia, and Alpha’s suffered a mysterious decline in health that had become serious by 1999. As it later transpired, Alpha’s mother’s former partner had been affected by the Tainted Blood scandal in the UK, and – despite a miraculous recovery after her HIV diagnosis and subsequent treatment – she became permanently disabled. She spent the following 17 years battling anti-retroviral medication side effects before her death in 2016. During this time, we were her carers and the coordinators of her support network.

Meanwhile, Alpha suffered a deterioration in her physical health as her ME produced new symptoms (including a type of thyroid-function collapse not detected by standard testing and hence undiagnosed for over six years, and alarming and unpredictable allergic reactions to an increasing number of substances) and Christopher started to show troubling manifestations of what transpired (in 2018) to be the hereditary condition, haemochromatosis. All in all, it was a diverting twenty years.

Elsewhere, by the late 90s, misunderstandings about us and the work as a result of our assumed connection to OA had become widespread. Given where we were in terms of the evolution of our work and artistic identity, the ‘Chris Hipkiss’ to whom proponents of OA referred was increasingly at odds with reality. Despite all that was going on for us personally, we were well aware that the misconception was not remotely to our benefit and were making every effort to break free of it. It was also absurd, for many reasons including the following:

By its very definition, the purpose of ‘Outsider’ art for its producers is assumed to be some kind of catharsis – an expression of, and release for, some inner turmoil or reaction to trauma, past or present. Our work – though very much borne out of our reactions to what’s going on in the world – comes from a light, shared space filled with humour and an enjoyment of one another’s company. Throughout all of life’s troubles, art has been our positive place, not an outlet for angst. There is no aspect of introspection at all and our process is the antithesis of ‘raw’ creation. Naturally, our early identity as a single male didn’t help our cause, but those who met us were well aware of our partnership and the environment in which the work was made.

In the same vein, the figures that appeared in earlier work were often described – with typical male-world-view assumptions – as female ‘objects’ while, in reality, they were icons for both our young selves. Between 1996 and 2006, they were primarily based on Brian Molko, an androgynous musician, whose style and voice inspired us. Before that, they were influenced by our frequent attendance at Pride marches. The last incarnations – just before we grew out of the need to populate our drawings with figures – drew on Lady Gaga and new ideas of fashion. Their meaning could not be further from the received assumptions, of dark and obsessive fixation, that constitute a strand of the OA canon.

Following on from our earliest drawings, our style had evolved quite quickly away from its graphic beginnings. By the mid-nineties, it should have been clear that there were intellects at work on the compositions, on the depth and richness of our use of the media and the addition of new elements, on the aesthetic quality of our output. Such attention to the viewers of our work and the world at large, we could have assumed, would naturally make us less appealing to fans of OA. But it’s a very sticky label; once its enthusiasts see it applied to an artist, they’re extremely reluctant to remove it.

Our bemused tolerance of the distortions made of us and our art faded when the culmination of events alluded to above meant that art sales became our only livelihood in the early 2000s. In 2006, we privately consolidated Alpha’s legal position in the partnership by registering the artist pseudonym ‘Chris Hipkiss’ (and later, ‘Hipkiss’) in her name. Our concerted efforts to correct our path and confine ourselves to the contemporary world were undoubtedly thwarted, in part, by our early miscategorisation, despite the help of our two galleries. We lacked agency not for the reasons usually associated with the ‘Outsider’, but precisely because we had been wrongly stigmatised as such in the first place.

In short, while we might have been gullible in having fallen for the ruses of those with commercial and/or reputational aspirations, the culpability for the deception lies only with them. We never assumed the mantles that they attempted to put upon us.

Christopher and Alpha Mason, circa 1992-3 (copyright Hipkiss. Do not reproduce without permission)

Success in correcting the error came gradually, but by 2011 we had largely escaped, declaring ourselves as the duo we have always been. In 2015, we dropped the confusing ‘Chris’ from our pseudonym with retroactive effect. However, a confected, parallel version of Hipkiss has continued to exist, with variations on early ‘Chinese whispers’ from our three-decades-old, self-penned article cited as historical fact.

When we accepted free publicity as any aspiring artist would have done, we were 28 years old, with no more than a few dozen works to our name and little notion of how we wanted to present ourselves. We treated the article as a creative project, not gospel writing. Nonetheless, we did not fabricate an ‘Outsider’ biography; we were careful not to actively categorise Hipkiss, while making our best attempt to fulfil a brief we did not fully understand, and which the editor himself now concedes should not have been offered to us. We were too young, and our artistic development was far too embryonic, for us to be branded.

At the heart of the matter is a habit common among individuals within this often cult-like corner of the art world, almost akin to scrap-booking or butterfly collecting, where the ‘story’ is part of the curio and the act of its collection freezes the item – in this case, a human being and their work – in time. This becomes highly contentious when an artist is alive and engaged, needless to say; it is an attempted hijack of someone else’s existence.

Speaking personally, only we know the facts of our lives – for example, the significance of and reasons for various decisions we’ve made, the impact of circumstances outside our control, what inspires us, the process of our dual creation and the dynamics and evolution of our relationship. Yet a couple of actors within the field have accused us of ‘rewriting history’ when we’ve corrected the sorry concoctions they’ve made of our lives and artistic practice – challenged the metaphorical tattered tabloid snippet they’ve guarded in their heads all these years – to reclaim our own past.

One Folk Art auctioneer claimed recently that we must have known what we were getting into with the Raw Vision article and had thus irrevocably labelled ourselves (ironic, since self-determination should be antithetical to one’s inclusion). According to this self-appointed judge and jury, we should serve a life sentence (and beyond) in the wrong genre for the crime of ignorance; one foolish mistake, almost thirty years ago. Many murderers spend less time in jail.

Even in less intentional instances, some purveyors have made such poor or non-existent attempts at research that they still describe us using a single male pronoun and obsolete pseudonym. For example, a GSCE exam paper included a question on the categorisation, citing our pseudonym among only three artists, clearly without any attempt at fact-checking, as recently as 2014.

While corrections to assumptions about who we are and how we should be classified are sometimes taken in good spirit (notably by private collectors), we have also encountered personal abuse and a refusal to face facts. Whether this is attributable to a particular psychological profile on the part of some of these collectors and dealers, we can only guess. One could hypothesise that, for them, the fact of having once bought or sold a work or two – even if their doing so did not directly benefit the artist financially – entitles them to claim a type of ownership of the artist themselves.

But what are they expecting, exactly? That the artist should accept the dissemination of false information about them, sit indefinitely in enforced silence for the sole benefit of someone who once acquired some of their work? Maybe we could pretend to fit the OA profile for the sake of the collector’s or dealer’s apparent integrity? These ideas are all, of course, ludicrous. In fact, there are laws that exist to protect our rights to refute inaccurate presentations of who we are as the creators. The fact that this kind of pressure to pretend to conform to OA ‘norms’ exists raises major concerns about the legitimacy of the genre as a whole. And ultimately, an artist is not to blame if a dealer has concocted an elaborate story to fit them to their specialism, or has sold a collector a pack of lies along with their work.

Interestingly, these types often share specific features in the expression of their anger – notably the baseless accusation, aimed at Alpha, of manipulation of the (helpless?) ‘outsider’, Christopher, a double-pronged insult that is misogynist to one of us and highly disrespectful to the other. In one example, a dealer would claim to know which of our works were the idea of one or the other of us, inevitably proclaiming ‘Alpha’s as inferior. Although we don’t work in such a delineated way, on the few occasions he hit on a work that was more one of us than the other, his assumption was incorrect (his reliable misapprehensions would be hilarious in other circumstances). In one recent case, we have been forced to take legal action against another dealer of this ilk who refused to stop pretending to represent us; having repeatedly ignored our requests over the course of some years, he finally engaged only in the form of personal diatribes of a similar nature.

The tendency to forego due diligence and dialogue with artists seems to be an extension of the DIY, art-world-rules-defying nature of the ‘Outsider Art’ ethos. In all likelihood, we are not unusual among artists in having started out unaware of our rights to control how and where our work is used. We now know that it is a requirement for institutions and galleries to sign an agreement before any show – in other words, to obtain the full consent of a living artist. A recent chat with a curator at Christie’s revealed that this is also the case with reputable auction houses. No institution in the OA world would consider such a ‘nicety’, and we never signed a contract with a gallery to entrust them with the right to act on our behalf.

Unfortunately, this slapdash attitude to artists (which is, without doubt, largely due to most of the big names being long deceased) has been unwittingly amplified by some highly-esteemed mainstream institutions. The invited curator of the exhibition, or the collector donating a collection or selling a work, is assumed to be somehow qualified to have labelled the artists involved. The Tate has recently become aware of their own errors in showing the Musgrave-Kinley collection so unquestioningly and has corrected them accordingly; the Whitworth, to which the collection was ultimately donated, has also worked to account for artists who should never have been included in the first place. However, not only are these cases rare, but the institutions should have obtained the necessary consent from any living artists before showing them in that context at all.

Fellow artists also fall for the anti-hype. In one example close to home, Turner prize winner Grayson Perry appropriated, blatantly and extensively, from one of our outsize early works, having spent – according to the curator – a considerable time scrutinising it at a NY show in 2005. Normally, the bigger artist would boost their less-well-known counterpart with a mention; such a courtesy was not forthcoming. A case of faulty memory, perhaps, or a failure to notice the original artist’s name? Not so. In 1999, in Perry’s more humble days, a link from his site to ours had enabled a collector friend to become acquainted with our work in the first place. What this story demonstrates is that art perceived as ‘Outsider’ is regarded – with a few big-name exceptions – as a free, homogeneous resource that can be cherry-picked à la volonté, with impunity, and sometimes wholesale.

Under intellectual property law, we alone can dictate how our work and the identity of its creators are to be credited. This applies to every work we’ve ever made. No outside party has the right to portray us or our art differently, and we retain both copyright and intellectual property rights even after the sale of the work. Should a dealer, auctioneer (or magazine, etc.) attempt to sell us under false pretences, please let us know.

To those who may run a site or blog, or are otherwise contemplating writing about this field of art, please take note of the foregoing facts and leave Hipkiss off your list of artists. If you are able to edit a past article to remove us, please do so. Should you have a public collection of this kind of art in which our work is included, please contact us to discuss how to proceed.

To those private collectors who have acquired our work under these banners, we apologise for the confusion and sincerely hope that you appreciate the art on its own merits. We are indebted to you for the support you gave us. It was never our intention to mislead and we have never personally done so.

For anyone looking to re-sell a Hipkiss they acquired within this context, by all means contact us for advice and the provision of a valid certificate of authenticity for the work. We are also building a database of collectors and would-be collectors of our older work with the possibility of buying and selling directly; please contact us for details.

Please note that auction houses such as Slotin Folk Art and Christie’s New York “Outsider Art” department – who define the genre as “art by untrained makers operating outside art world establishments”, a description that clearly excluded us from the time of our very first exhibition – are aware that they should no longer include, and never should have included, our work. This applies equally to galleries of the genre, who have no legal right to publicise our work for exhibition and/or sale and thereby perpetuate the same old misinformation.

Please find a list of our approved agents here.

Notes and Addenda:

1: Nodopaka, A (2015), Vayavya, Winter

2: We appeared in Issue 9, when the magazine’s main subtitle was “International Journal of Intuitive and Visionary Art”, with sub-categories listed as “Outsider Art, Art Brut, Self-taught Art, Contemporary Folk Art” – Raw Vision Issue 9

3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raw_Vision

4: Windsor, J (1995), ‘The Outed Outsiders’, The Independent, 1 May

5. Steward, S (2000), ‘Outsider dealing’, The Observer Life Magazine, 29 October, 28-36

6. Frank, P. (2015), ‘Artists Discuss The Problem With The ‘O’ Word’, The Huffington Post (Arts & Culture) (web), 21 May

7: Note: the account of Ms Kinley is not a case of speaking ill of the dead. We were stunned by the contents of “Monika’s Story” when it was published and immediately contacted her to ask why she had chosen such a false portrayal; to condense her time with us to a fictional one-page account of a child-like drifter who had approached her in wide-eyed supplication was an astonishing fabrication. Her only defense, and only to the one complaint of describing Christopher as single, was that she thought Alpha had wanted to keep a low-profile due to her PhD studies – but at no time had we suggested that an acceptable way around it was to erase our relationship altogether. Regarding her demeaning depiction of Christopher, she could offer no explanation and no apology. We had to accept that we had been betrayed for her purposes; sadly, this episode marked the end of our contact with her. As long as her book remains available for sale, our denouncement of its contents concerning Hipkiss must also remain public.

8. 2006 Parallel Visions II, The Galerie St. Etienne, New York, NY, exhibition guide

9. Johnson, K (2000), ‘Visionaries who portray reality from the outside in’ and ‘Review: Hipkiss’, New York Times, January 28, E35 and E37 (paywall) – questions whether Hipkiss work is made by “… the hand of a trained graphic artist mimicking the look of visionary Outsider Art.”

10. Hambrook, Colin (2006) review of ‘Inner Worlds Outside’, Disability Arts Online

11. Rexer, L. (2006), ‘Art and Obsession’, Art on Paper, May-June Vol 10, No.5, 56-63: “We have already seen, in reference to insider artists, how problematic such judgements can be; [Chris] Hipkiss’ pencil allegories simply render such ideas irrelevant. The five-foot-long (sic) Lonely Europe Arm Yourself straddles the line between science fiction and medieval apocalyptic tub thumping. It might seem obsessive if so much weren’t clearly riding on it. Hipkiss’s art is open-ended, not circular. It doesn’t close itself off, but seeks the widest possible audience. The desire is confirmed by the artist’s detailed informative website…”

12. Update July 2023: We refer particularly to Intuit (The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, Chicago) here; they mounted an enormous solo exhibition of our work in 2008, borrowing from multiple collectors, taking immense care to hang the work and even footing the bill for repairs in some cases. The problem? We were not informed that such an event was even taking place until it was far too late to prevent it. The materials for the show – a catalogue, a talk and an article in the Center’s magazine – were all produced without our input or approval. Despite our requests, we were never privy to a transcript or video of the talk, so have no idea, to this day, what was said about us – specifically, how on earth it was implied that we fulfilled the Center’s remit. This year, we were finally able to speak with someone at the Center concerning the unlawful nature of the show. The present staff acknowledged our complaint and kindly removed all references to the exhibition from their site and social media accounts. Two small works that had ended up in their collection were subsequently auctioned (in a sale of contemporary art). Thank you, Intuit.

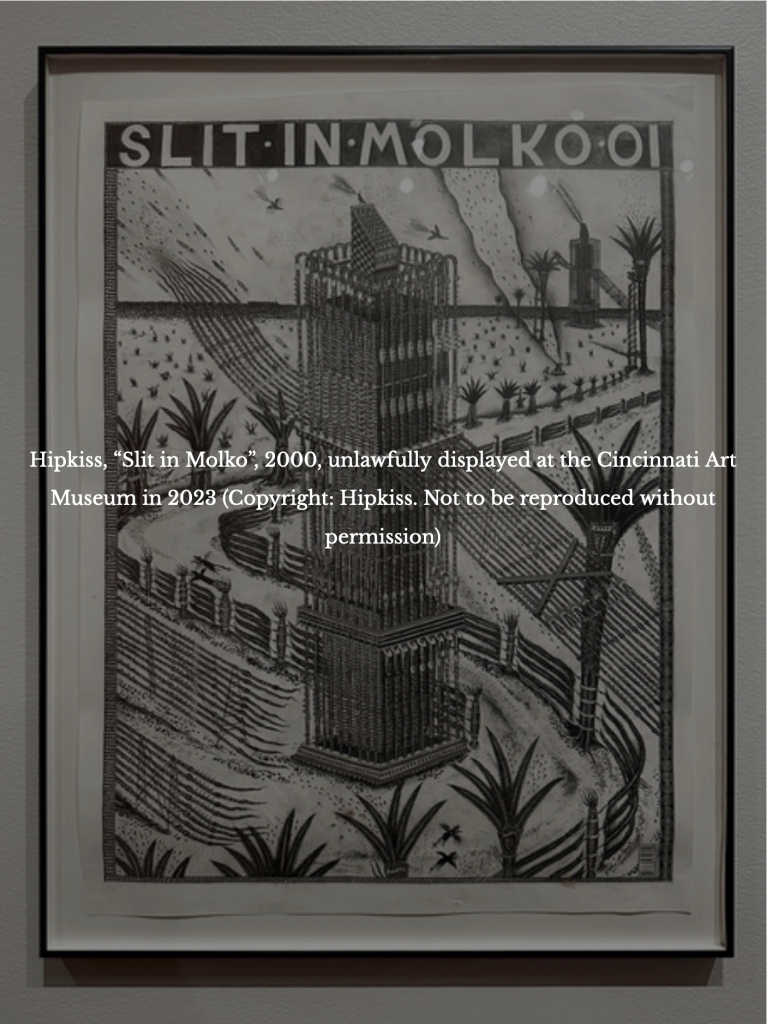

13. This situation developed such that it warranted its own dedicated post. See “Creating Connections: Self-Taught Artists in the Rosenthal Collection” at the Cincinnati Art Museum

All content copyright of Alpha & Christopher Mason, 2021. Not to be reproduced, in full or in part, without permission.

Further reading:

Jonathan Griffin’s critique on Sotheby’s blog, August 2020

A no-holds-barred essay by Adam Geczy

Frank Maresca’s definition from inside the ‘Outsider’ world: Artspace, December 2012

On the rights of artists and their estates: Artnet magazine, 2 August 2022

On the aspects of potential fraud and scams: Alec Luhn in The Telegraph, November 2019

On defamation: Hagai Aviel & René Talbot discuss the ethics of the misappropriation of art in psychiatric settings in the journal Mad in America, March 2022

An article offering advice to collectors considering investing in OA – Mutual Art, August 2023 – in which even living artists are described in terms of dead commodity.

This post is a personal account of our experience, from a Western-European perspective; here, the (mis-)categorisation of artists under these banners tends to be justified by its purveyors via pseudo-paternalistic, projected notions of class, education level and mental health status. We are not qualified to comment at length about the complexities of the labeling in the US, where race can be decisively added to the list. Artist Kevin Sampson spoke to Priscilla Frank of the Huffington Post on this subject and the article (June 2016) is well worth a read.