An exploration of all that’s wrong with this kind of categorisation in art, with a side-dish of copyright infringement, conscious abuse of Intellectual Property rights, image theft, outright dishonesty and a supersized sense of entitlement on the part of a respected institution.

This post started out as a footnote to our pinned entry, “The miscategorisation of the artist Hipkiss: a correction, a critique and the cautionary tale behind the error”. It concerns the actions of CAM, whose curators included a work of ours, without permission, in a show and catalogue devoted to art by amateurs. For professional artists reliant upon our reputation for our livelihood, this was evidently problematic. A revelation on the 25th September, thanks to a museum visitor’s draft blog entry, dictated that we shine a brighter spotlight on this shameful story. We will firstly detail the problem with our inclusion, before exploring the wider questions these kinds of shows should prompt one to ask.

We’ve had a good couple of years in terms of publicity: a ten-page interview with a French culture magazine, our inclusion in the landmark Thames & Hudson book, ‘Drawing in the Present Tense’, a feature in Fukt magazine and an upcoming appearance in a critic’s collection of environmentally-focused contemporary artists in France. This followed on from our solo slot at The Drawing Center in NYC as well as shows at two French FRACs and the Jenisch Vevey Museum in Switzerland, and fledgling relationships with two new galleries. We have been busy working for an upcoming solo show at the beautiful new NYC space of GAA.

In a more general sense, however, 2023 got off to a bad start, with the deterioration and death of Christopher’s father, followed by the realisation that his estate had been left to fall into criminal hands in southern Spain. For complex reasons, dealing with the fallout has not been easy and is ongoing at time of writing. Meanwhile, we’ve been suffering the kind of dip in sales revenue that seems to be affecting our echelon of the art world in general. Added stress was not required and one thing we didn’t expect was a major institution to commandeer our work for an exhibition of ‘Self-Taught’ art. We thought this misunderstanding was very much in the rear-view mirror.

In June, we were alerted by an academic friend of ours to the inclusion of our work, without permission, in an exhibition entitled “Creating Connections: Self-Taught Artists in the Rosenthal Collection” (June 9 – October 8 2023) at the Cincinnati Art Museum; the documentation makes it clear that the title’s adjective is used as a euphemism for Outsider Art. This is not the first time that the presence of our work in a private, largely-OA, collection has resulted in an art centre including us in such shows, though usually under the pseudonym “Chris Hipkiss” and due simply to poor research; though not lawful, the centres concerned have been minor ones.

However, in this case, our site-visitor stats show that the personnel of CAM, a revered institution, took the time to crawl all over our website several times (including the contact page, which would have enabled them to email us), referred to us correctly as a couple known as “Hipkiss” and stole a picture of us from Google without checking the copyright to which it is subject. From our site they could easily see that we should not be so labelled; anyone doing their job properly would have thought it a good idea (nay, essential) to contact us to check that it was OK to use our work and identity in this way. They did not.

Dr. Julie Aronson, the curator who responded to our complaint (not a specialist in OA), was unapologetic (“sorry if you feel…”) but said she was removing the work from the walls, along with an information panel featuring the stolen image of us. She also had the visitor guide edited to remove us. In doing so, she acknowledged that our inclusion was illicit and that we had the right to veto it. At the time, that left only the bigger problem of a catalogue that was produced for the exhibition. In response to our demand that something be done to mitigate the disinformation the publication will spread, Dr. Aronson bluntly referred us to a lawyer for any further communication, knowing full well that we are not US residents, so have no way of hiring someone pro-bono.

Furthermore, she failed to supply the requested PDF of the catalogue pages concerning us and we have not been sent a copy, so we have no idea exactly how our very non-OA biography has been twisted to suit the show’s requirements. That said, of course the major problem with the catalogue is our having been included in it at all. It is widely available online – second-hand copies are already circulating – and is likely to keep misleading people well into the future, encouraging countless others to make the same ‘mistake’ the curators did here.

Dr. Aronson’s excuse in her first response to our complaint was that she had been unable to contact us – this, despite the ‘mailto:’ link on our site having been clicked by someone at the museum, despite our presence on Instagram, LinkedIn, dear old Twitter (RIP) and even Facebook, not to mention our galleries, who would have willingly put her in touch if she couldn’t work out the other methods and, lastly, the fact that she was working at the time with Charles Russell, with whom we’ve been in contact for years. In short, this explanation was a blatant lie, just as her referring us to a lawyer was a brazen attempt to silence us.

Incidentally, Dr. Aronson claimed to have been in touch with ‘all the other’ living artists. We can’t say for sure whether that’s true, but she thought fit to add a little joke to the effect that she would have liked to have sent us an invite – but we wouldn’t have wanted to come anyway as it turned out! Very funny.

Throughout the intervening period, we had assumed that the catalogue was our only remaining problem, albeit a significant one. We made regular checks of the visitor guide on the site to ensure that we had not been surreptitiously reinstated. Surely a museum such as CAM would not have lied about removing our work? Well, they – or rather, the respected museum curator, Dr. Aronson – did just that.

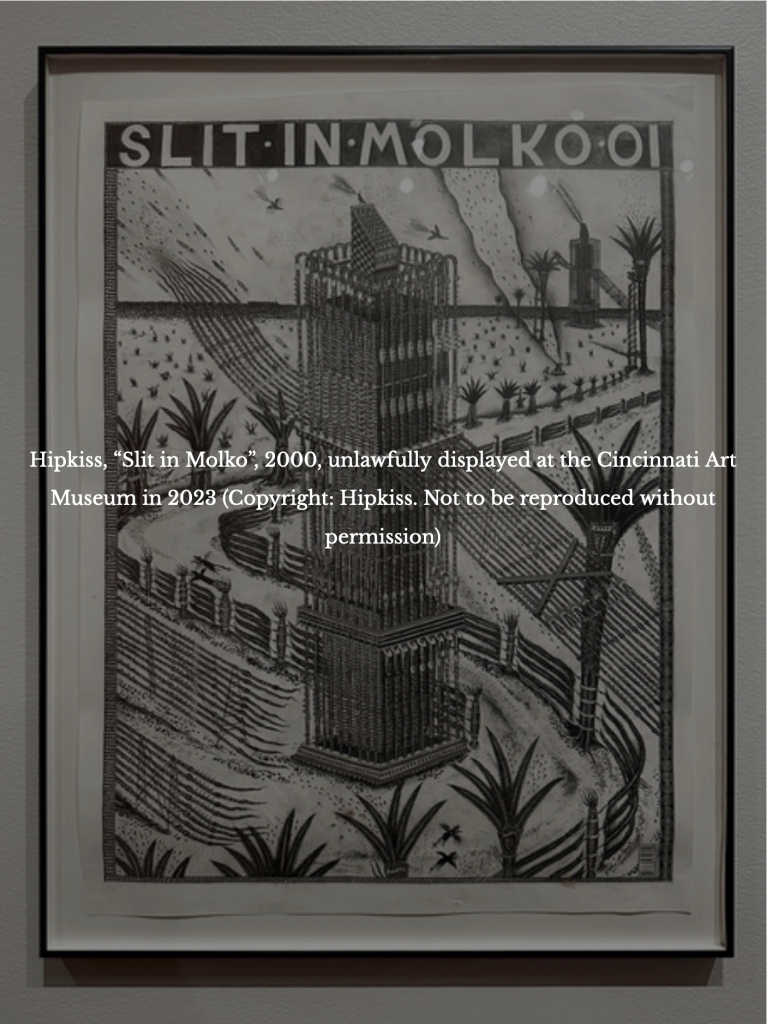

On the 25th September, we found a courtesy back-link to our site from a blogger who had written a thoughtful entry on our reported preference for the description ‘Truant’ for artists who eschewed traditional art school; the sentence that the curators used came from an old interview. The blogger also included an image of our work “Slit in Molko 01” (which the museum staff had seen fit to rebaptise “Slit in Molko Oi”; ‘Oi’ is a rather silly sound to a UK-English ear). Next to the work was a plaque containing, it seems, the same text and, presumably, picture of us (stolen, remember) that was in the visitor guide.

We wrote to the writer, catching the post before it went live, and were informed that they had visited the museum and seen the work just two days before. We remain very thankful to them both for alerting us to the fact and for pulling the intended blog post.

[As an aside, what this demonstrates, apart from the more obvious problem, is how an error like CAM’s can have repercussions years into the future, as blog images and posts – no matter how intelligently written and with what nuance – are shared on sites such as Pinterest along with inappropriate labelling. We have spent far too many hours of our precious lives having such illicitly shared images removed.]

When confronted with the reinstatement of the work (or failure to remove it as she’d declared she had), Dr. Aronson, along with her co-curator (and the Chief Curator of CAM) Cynthia Amnéus, refused to reply to our request for an explanation. We must assume, furthermore, that our continued absence from the visitor guide – the only documentation of individual artists available online – was deliberately maintained to fool us. Two lies, one threat and continued premeditated deception. We remain stunned by this behaviour.

The misuse of our work and identity in these circumstances and in this context, without the necessary permissions granted, already amounts to a gross assault on our rights as artists. Unfortunately, it also demonstrates that even within more prestigious institutions, and in an era in which it is extremely easy to perform the necessary due diligence, the OA categorisation is regarded by vaunted curators as an excuse for a holiday from their responsibility to living artists.

CAM also holds the dubious honour of being the first such institution to extrapolate the imagined and imaginary OA credentials of a presumed-male artist called “Chris Hipkiss” to a woman named Alpha Mason, as part of a duo under a different name, on the basis of no evidence whatsoever. Incidentally, Christopher Mason has equally never been referred to in this way. Part of the reason we changed our pseudonym, long after we retroactively declared ourselves a duo, was because it was the name “Chris Hipkiss” that had been mistakenly associated with these labels in the first place.

Though clearly the main victims of this series of events, we are not the only ones; our galleries are aware of what happened to us in times past and are extremely supportive. They have nothing to do with these categories of art, and the type of confusion – generated by the parallel, ghost identity and the continued drip-feed of this set of falsehoods – risks impacting them too.

We wrote to Richard Rosenthal via his Foundation, explaining the situation and asking him to intervene, with a reprint of the catalogue. We have no idea if he received the letter or what he thought of it if he did. We would not cast aspersions by suggesting that he ordered the reinstatement of the work, if it had been removed in the first place, though we sincerely hope that wasn’t the case.

What we do know – and this is a general point, not confined to OA or to this particular scenario – is that there is a common misconception that becoming the owner of an artwork allows one to do anything one likes with it.

It’s true that the physical work belongs to the buyer; in that respect, they’re more than welcome to store it in a damp attic for years, burn it or shred it to use as hamster bedding – as long as they don’t publicise a film of themselves doing it without the permission of the artist, thus potentially infringing upon the rights that the latter always retains. These are (among others, depending on the jurisdiction) copyright and Intellectual Property rights which prevent the denigration of a work or its author or its inappropriate and/or unauthorised public display. It’s important to note, furthermore, that even if the artist is a perfect fit for an exhibition, it is still their prerogative to deny permission and have the work removed.

We’re not in any way implying that artists don’t appreciate collectors buying their work or curators choosing to exhibit it; of course they do, and we are no exception, but problems sometimes arise as they have here. The blame for any breach of artists’ rights in displaying their work, or using their copyright images in a publication, without authorisation lies rarely-to-never with the collector and almost invariably with the curators. It is their job to ensure consent – and respect the artist’s wishes in the absence of it. In this instance, we remain indebted to Mr. Rosenthal for having acquired our work and strongly suspect that this series of events is entirely the fault of the curator(s), with whom the buck stops.

Dr. Aronson implied that museums are somehow exempt from some of the constraints that artists’ rights impose. In this, she is wrong; while it should be hoped that such institutions would not breach those rights due to the reasonable expectation of an awareness of them among art historians, it’s principally because they would be hard-pushed to do so in such a way as to defame an artist in the vast majority of contexts.

This is where the subject of this particular exhibition puts the matter in sharp relief, and where we come to the wider issues for all the living artists included, with or without the proper consent. There aren’t any real-life parallels, and this is an audacious and theoretical one, but imagine that a curator decided to mount an exhibition of art made by convicted paedophiles. If an artist were to be included despite having no such history, their indignation (and potentially legal action) would be inevitable and no curator would risk it. In a similar vein, no professional artist would want their work passed off as being by an amateur, risking its devaluation and damage to their reputation and career opportunities. The inference has a direct affect on whether or not other curators/gallerists/academics choose to contact the artist.

In the CAM exhibition, the non-professional status of the artists (if they’re aware that what they’re creating is art at all, goes the familiar refrain) is overtly stated in the associated materials. The following statement appears in the visitor guide: “The term ‘Outsider Art’ dates to the 1970s and is still used in the marketplace to denote work made in isolation by those at the margins of society.” It’s a pretty concise definition – rather like Christie’s description of “art by untrained makers operating outside art world establishments“. (Italics, in both cases, ours.) We don’t need to repeat ourselves; we described in detail how absurd it is to try to crowbar us into these categorisations in the pinned post linked above. But what also strikes us is the almost triumphant finality in the specifics of the pigeonholing; the inference is that if one ever really is isolated ‘at the margins of society’ or ‘operating outside art world establishments’ then that is where one belongs. How incredibly damning.

Let’s take a look at some of the expressions used by the curator of the CAM show in the press: on Fox TV (25th May), Dr. Aronson started the generalisations and implication of the non-professional status of the artists by saying that in their process “whatever they have handy they can use”. On the 25th September – the very same day on which she ignored our request for an explanation of the continued presence of our work in this setting – she spoke with WXVU News Radio, admitting that “Self-Taught” is not a good term but still using it, interchangeably with “OA”, to denote art made by amateurs. To really stick the knife in, she also referred to this kind of art as “still affordable” (presumably because, since the artists are either dead, don’t think they create art and/or may be in institutional settings, they don’t have the need or expectation of being justly rewarded for their travails. Or she just thinks it’s all rubbish).

The opening lecture (June 8th) was by Professor Olivia Sagan, a psychologist and expert in art therapy from Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. She apparently wrote an article in the catalogue, of which we’ve yet to receive a copy (have we mentioned?). One of her main specialities is researching the processes of art-making by people with mental health issues, in institutions, etc. Again, blanket statements were made about the artists in the show – Hipkiss implicitly included, obviously. She described their creative process, as usual, as being divorced from intellect and intention. This reduction of creativity to a primitive, almost animalistic, instinct is a feature of many talks and texts in the field. Apart from the generalisation – from a therapy situation to folk artists and even people like us – it displays, again, a distinct air of condescension.

Part of Professor Sagan’s brief was to introduce a sister exhibition, entitled “Visionaries and Voices”, featuring ‘creators with disabilities’. Connecting these two exhibitions betrays a common assumption that is frankly insulting to these genuinely amateur artists: that due to their ‘disability’, the best they can hope for is the second-tier success of known OA artists who, themselves, would never be considered worthy of a solo exhibition at the institution.

Of course, we have no problem at all with our work being shown alongside that of people creating within an art therapy context – why would we? The problems we have are, firstly, that those creators should be ghettoised and have limits set on them in terms of their own potential and, secondly, that our work should be there only because a curator has tried to shoehorn our biography into a suitably OA model due to a historical mistake. Also – as is often the case – that we should be the only professional living artist in such a show.

The original PDF visitor guide, in which the curator made her best efforts to make Hipkiss sound a little bit ‘nuts’, highlights the wafer-thin justification for this kind of exhibition. We have seen a few of them, all with the same stated intent to ’empower marginalised artists’; some have had the courtesy to ask us before trying to include us. You can see the visitor guide as it now stands from this link. In fairness, there has clearly been an attempt to avoid the morbid language around trauma, tragedy and criminality that dominates dealers’ (and some institutions’) spiel in this field. But it warrants a little unpacking.

Our portrayal was ostensibly cited and above board, but as seasoned observers of this field, we spotted the usual ploys straight away: in snippets of texts plucked from our website and an old interview with The Huffington Post, we speak about our use of pseudonyms and, in a subtle turn of phrase equally common in this context, we apparently ‘reject’ the term OA, rather than its just being wholly inappropriate (the whole thrust of the HP article, ironically, was the journalist’s observation that calling Hipkiss OA was nonsense; funnily enough, this crucial fact was not ‘plucked’).

The choice of the word ‘reject’ exposes the previously discussed pseudo-paternalistic attitude of the self-appointed arbiters of OA, be they full-time or ‘just visiting’, as in this case: It’s code for “Say what you want, but we know best.” Any notion of autonomy, as an artist or even as a human being, is denied. From the more entrenched pro, there is another level of attitude that comes to mind – one we’ve actually heard articulated: “How dare you contradict me, after all I’ve done for you…”. In other words, be grateful to be stuck in that hole I’ve put you in; you’d be nothing without me…

However, what really stands out, despite the efforts of Dr. Aronson, is the absence of any anomaly in our little ‘bio’ compared with most of the others. It states that we met at a London university and work only together – hardly fitting the definition of ‘marginalised’ artists ‘working in isolation’, then. However, in another use of OA code, quotes from the HP interview – conducted when our joint pseudonym was still “Chris Hipkiss” – are credited to “Chris”; in the article, this referred to both of us. The use of the diminutive name of Christopher here implies to the reader that the curator is personally acquainted with us. This may have been sheer carelessness and inattention, but we have our doubts; it’s a common trick used to indicate that the little artist is ‘taken care of’. A fake air of warm and cuddly vibes, in other words.

Of course, the text also fails to mention our extensive CV; no effort was made to contact or quote the numerous, some very eminent, curators and academics that are (genuinely) acquainted with us and the evolution of our work over the years (artistic evolution being the antithesis of OA). Nothing was taken from the information about us from our galleries’ websites. Who needs truth when formulaic waffle and cherry-picked snippets will do? Still, there is no element that overtly explains our inclusion in the grouping.

As for the other creators, notwithstanding our comment above about the relative lack of darkness in the descriptions of their lives, other than Jean Dubuffet (the root of it all; without him, these shams of classification would probably not exist), there is some statement in every bio but ours to indicate why they’re in the show. There is a good sprinkling of ‘visionary experiences’, menial employment, incarceration, institutionalisation, ‘relieving feelings of…’, schizophrenia, pogroms, slavery, racism, abject poverty, reactions to bereavement, HIV and, of course, using found materials. There was a nod to this even in the description of our work: apart from graphite and silver ink, the media list includes ‘brown paint or resin’. Crazy artists, eh? It’s clearly two drips of coffee. We might have been careless, but we hadn’t gone to the trouble of ‘finding’ some form of gunk to purposely spoil an otherwise well-thought-out composition, driven by some aspect of our tortured souls.

Come to that, and as we’ve probably said before, why is a morbid fascination with the misery people suffer OK? Why is there this drive to reduce people to their worst life experiences? Without the superimposed ‘biography’, would the art have its own merit? This is a question we’ve found ourselves asking collectors that bought our work under false pretences, usually with no response. In some cases they’ve become quite angry that we won’t just stay quiet and sit in the box the dealer gave them for us. Our point here is that it’s easy to invent and condense someone’s life into a suitable pod of info, fake or otherwise, but what does it say about someone’s critical faculties should they rely solely on these criteria to appraise an artwork’s quality?

Notable, too, is that many of the artists in the show are actually ‘Folk’ – not ‘Outsider’ at all – but the same kind of attempts are now made to highlight adversity in their bios. Would they have seen themselves in that light? Could they have just been painting for pleasure? Is it for any of us to say? A corollary to that is that, as usual, most of the showcased creators are long dead, so have no voice.

As so often, the curators have encouraged visitors to ask themselves questions as they view the show. Suggestions include: “What qualifies as museum-worthy art? Why are these works grouped together when they are so dissimilar? Does knowing the artist’s biography enhance your appreciation of works of art?” We’ve probably covered most of the answers in this post, if not in the detached, faux-benevolent way CAM were envisaging; the freak-show attractions themselves aren’t supposed to comment on their lot, after all. But we can’t help imagining the puzzled look on the face of at least one discerning visitor, having Googled or DuckDucked our name to find a living, working artist couple whose art has evolved significantly since making the piece they see in front of them, asking themselves if it’s not all just smoke and mirrors.

Perhaps the most ironic part of the literature for the show is the plea for the end of all such labelling: “Can’t we just call it art?” Well, CAM, in all these years, we’ve heard this stuff from every institution that’s put a similar show together. Why don’t you start? Split the groupings up; put these artists individually in shows that don’t revolve around the outdated and insulting labels? We’re not holding our breath. It’s pure exploitation – of the creators still living, genuinely amateur or otherwise, of the memory of the dead, and of the hoodwinked visitors.

Should you own a copy of the catalogue or borrow one from a library, bearing in mind that the use of our IP was non-consensual and unlawful, you have our full permission to cut out the pages including Hipkiss’ copyright images and/or associated text and shred them. What you choose to do with the rest of the book is, of course, up to you!

Before we put this post to bed, here’s a little history of the work at the centre of this post. It is dominated by the regular themes and motifs we were using at that time. The central tower and pipework fences were inspired by our recent visits to New York – a mecca for any frustrated architect; we both dream of complex buildings in our sleep. It’s a simple composition, exploring the idea of movement around static elements, though our perennial desire to play with perspective and juxtapose regimentation with meandering, organic forms was evident. The work was made in our Kentish (UK) cottage. Until it appeared in this show, we had no idea that it had made the trip across the Atlantic and into the Rosenthal’s collection.

The title references Brian Molko, the frontman of the band Placebo, whose first two albums were played on rotation in our house along with Portishead, Hole, Pussy Galore and REM at that time. Molko’s look, meanwhile, was the basis for many of the talismanic, alter-ego figures with Louise Brooks haircuts that appeared in our work back then. We credited his unwitting ‘input’ via titles like this a number of times.

The work was featured in a solo exhibition at England & Co., a London gallery of contemporary art, in 2000. It was the private view of this show that we attended handcuffed together, as mentioned elsewhere, having become exasperated at being split apart at previous vernissages. The catalogue, to which we contributed a text, referred to (the then) “Chris Hipkiss”, in passing, as self-taught in the literal sense of not having attended traditional art college. We’re not sure when Mr. Rosenthal acquired the drawing; we don’t recall meeting him at the opening, but it was well attended, so there is every possibility that he was there. Had we known how the language was to be skewed over the years so that artists like us were caught up in the constructs of others, we would undoubtedly have been more proactive in ensuring that collectors such as he were not furnished with a picture of us that was so very far from the truth.

All content copyright of Alpha & Christopher Mason, 2023. Not to be reproduced, in full or in part, without permission.

One thought on ““Creating Connections: Self-Taught Artists in the Rosenthal Collection” at the Cincinnati Art Museum”